A Raytracer in Python - Part 1 - Basic Functionality

Some time ago I visited Sydney, and I made a tragic mistake: I entered the University bookshop. Why a mistake, you say? I am book maniac. As soon as I enter a book shop (live or on web) I end up spending up to a thousands euro every time. This time, it was not the credit card, but the limit of 20 kg on my luggage to put a limit on what I could buy. Needless to say I got really good stuff, in particular this 761 pages of pure awesomeness: "Ray tracing from the ground up". This book teaches you how to write a raytracer, step by step from a first basic skeleton to incredibly complex optic effects. It also provides code, available for download under GPL. I haven't downloaded it, but according to the book it's in C++. Since I want to keep myself fresh with python, I will write my own version in this language.

The first objection I may hear is performance. Native python is much slower than C++. I agree, and I do it on purpose. My objective is in fact not only to write a raytracer for fun (and the world is full of already awesome raytracers), but also to perform some infrequent python exercises: interfacing with C, parallelization and, hopefully, some OpenCL programming. This is my hope, at least. I will try to spend some time on it and see how far I can get.

All the code for raytracing is available on my github

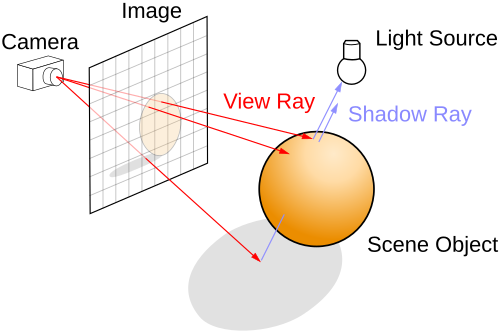

What is raytracing and how does it work ?

Raytracing is a technique to produce a photorealistic image. It works by projecting rays from the observer to the scene, and coloring pixels on a viewplane for every ray that intersects an object.

This mechanism resembles how vision works, although in the opposite direction. Light rays from a lamp hit objects and their reflection happens to scatter around. Some of these reflections will enter our eyes and allow us to see the world around us. Doing the opposite, tracing from the observer, is clearly more efficient as we don't care about the rays not hitting the observer (at least in its basic implementation), only those who do.

Performing raytracing (or to be more accurate, for now just its basic form raycasting) involves the following steps:

- define a geometric object in space, like for example a sphere

- define a view panel made of pixels

- shoot one straight line (ray) from the center of each pixel

- if the ray intersects the object, mark the pixel colored, otherwise mark it with the background color

That's it. Basically, it's an exercise in geometry: finding intersections between lines and 3D objects in 3D space. In code, it becomes:

from PIL import Image

import pygame

import math

import numpy

import sys

epsilon = 1.0e-7

class Sphere(object):

def __init__(self, center, radius):

self.center = numpy.array(center)

self.radius = numpy.array(radius)

def hit(self, ray):

temp = ray.origin - self.center

a = numpy.dot(ray.direction, ray.direction)

b = 2.0 * numpy.dot(temp, ray.direction)

c = numpy.dot(temp, temp) - self.radius * self.radius

disc = b * b - 4.0 * a * c

if (disc < 0.0):

return None

else:

e = math.sqrt(disc)

denom = 2.0 * a

t = (-b - e) / denom

if (t > epsilon):

normal = (temp + t * ray.direction) / self.radius

hit_point = ray.origin + t * ray.direction

return ShadeRecord(normal=normal, hit_point=hit_point)

t = (-b + e) / denom

if (t > epsilon):

normal = (temp + t * ray.direction) / self.radius

hit_point = ray.origin + t * ray.direction

return ShadeRecord(normal=normal, hit_point=hit_point)

return None

class Ray(object):

def __init__(self, origin, direction):

self.origin = numpy.array(origin)

self.direction = numpy.array(direction)

class ShadeRecord(object):

def __init__(self, hit_point, normal):

self.hit_point = hit_point

self.normal = normal

class Tracer(object):

def __init__(self, world):

self.world = world

def trace_ray(self, ray):

if self.world.sphere.hit(ray):

return (1.0,0.0,0.0)

else:

return (0.0,0.0,0.0)

class ViewPlane(object):

def __init__(self, resolution, pixel_size):

self.resolution = resolution

self.pixel_size = pixel_size

def iter_row(self, row):

for column in xrange(self.resolution[0]):

origin = numpy.zeros(3)

origin[0] = self.pixel_size*(column - self.resolution[0] / 2 + 0.5)

origin[1] = self.pixel_size*(row - self.resolution[1] / 2 + 0.5)

origin[2] = 100.0

yield ( Ray(origin = origin, direction = (0.0,0.0,-1.0)), (column,row))

def __iter__(self):

for row in xrange(self.resolution[1]):

yield self.iter_row(row)

class World(object):

def __init__(self):

self.viewplane = ViewPlane(resolution=(320,200), pixel_size=1.0)

self.background_color = (0.0,0.0,0.0)

self.sphere=Sphere(center=(0.0,0.0,0.0), radius=85.0)

def render(self):

pygame.init()

window = pygame.display.set_mode(self.viewplane.resolution)

pxarray = pygame.PixelArray(window)

im = Image.new("RGB", self.viewplane.resolution)

tracer = Tracer(self)

for row in self.viewplane:

for ray, pixel in row:

color = tracer.trace_ray(ray)

im.putpixel(pixel, (int(color[0]*255), int(color[1]*255), int(color[2]*255)))

pxarray[pixel[0]][pixel[1]] = (int(color[0]*255), int(color[1]*255), int(color[2]*255))

pygame.display.flip()

im.save("render.png", "PNG")

while True:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

sys.exit(0)

else:

print event

w=World()

w.render()

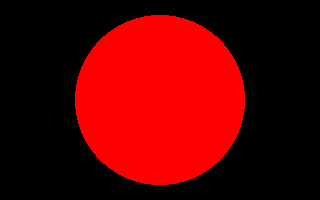

The result is intriguing:

Ok, I have a very loose definition of "intriguing", but it's a start.